If you’re one of the three people who’ve read my posts, you’ll know that I believe (a) cheating is going to happen, (b) there’s nothing we can do about it. You should also get the impression that (c) I’m not too worried about it. Don’t we always say “Cheaters only hurt themselves”? If we say it, shouldn’t we stand by it?

But academic dishonesty is an issue: we want the “A” to really mean “good work” and not “knows how to defeat webcam monitoring.” The way forward is through:

We have to scrap the notion that exams in ANY form are meaningful evaluations of a student’s knowledge.

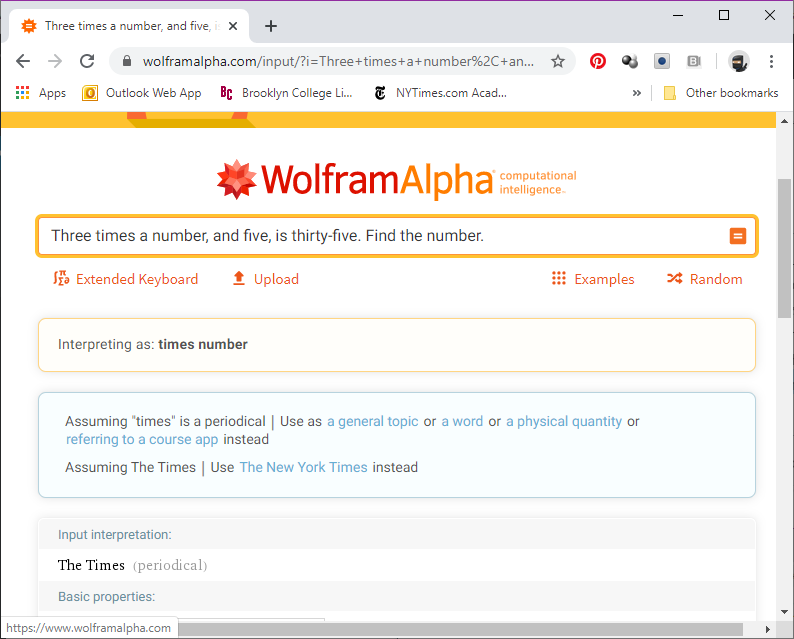

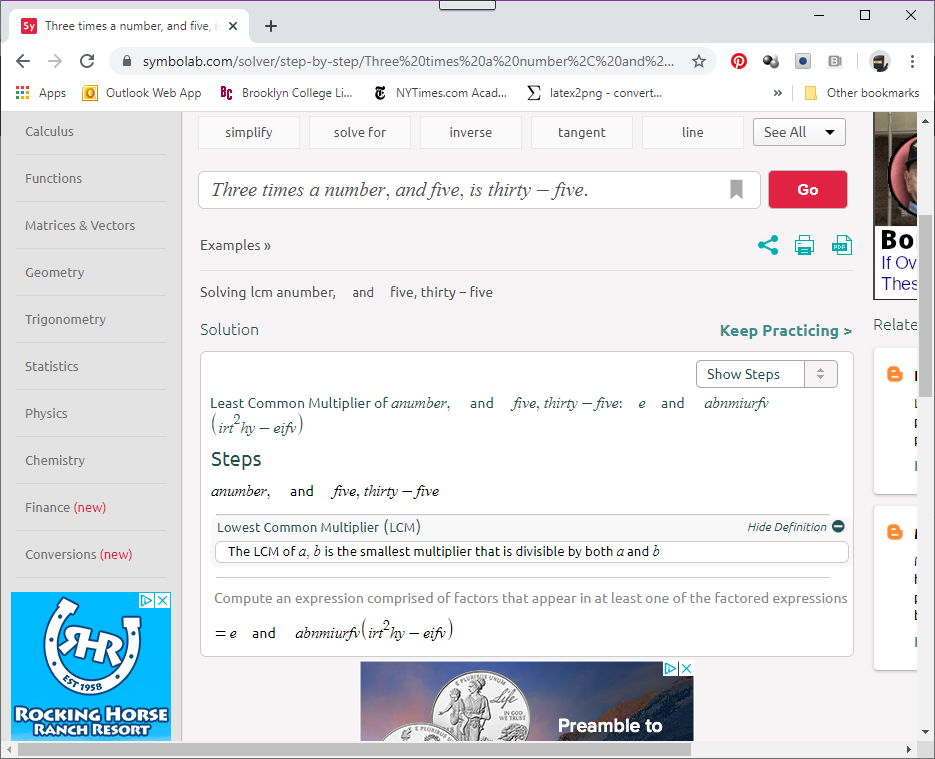

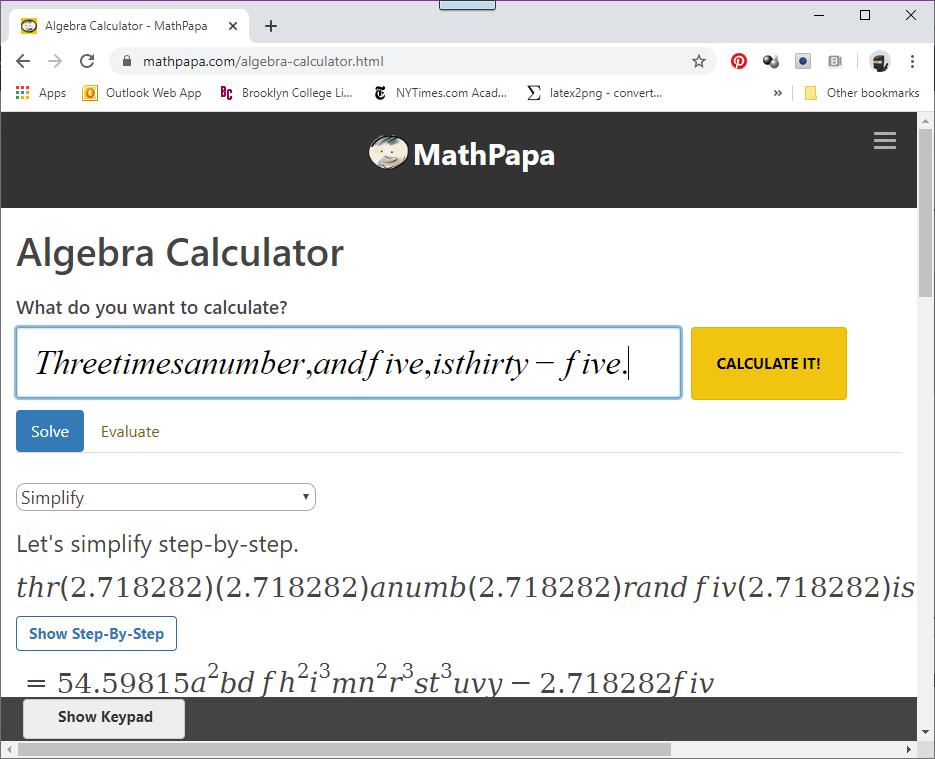

If your department has common finals, try this exercise: take the most recent final you can find. Then type the questions, exactly as they’re presented, into Symbolab (or Cymath, or Wolfram Alpha, or Mathpapa). See what grade a free internet app would get on your final exam. If the free internet app can get a passing grade on the final, what does this say about the student who can do the same?

I don’t know what it says to you. But what it says to the student is that your class has the value of a free internet app. And the question we hope they don’t then ask is, “So why did I pay $4000 for the course?”

So what can be done? The obvious solution is making sure that no internet app can solve a question you’ve asked. That’s easy: just make every question require the student to do a Ph.D.-level dissertation. Of course, most students would end up failing such exams, and an exam that fails everyone is a useless exam. (An analogy that’s helpful: If you want to evaluate the physical fitness of a group of people, you could have them run a 100 mile marathon. Those who cross the finish line are in great shape! But the test tells you nothing about those who fail to cross the finish line)

While you couldn’t write Ph.D.-dissertation questions for a final exam, it does at least suggest a way forward. The thing about a Ph.D. dissertation is that it relies on putting together a lot of little things, over a long period of time. It’s a project, in other words.

In the age of the internet, we must move towards project-based evaluation.

The problem is that doing so is very difficult, especially if you haven’t trained your students to do projects. Telling them, three weeks before the semester ends, that their final evaluation will be a project will cause riots, especially this semester when everything else has changed. Be kind to your students: live with the fact that your final exam is effectively going to be an open book, open note, open internet exam, and accept that some students will get 100s even though they should be getting 30s.

But next semester…now is the time to start thinking about what those project-based questions are going to be. What sort of problem requires putting together everything from the entire semester, and can’t be answered by typing the problem into Wolfram Alpha? (Modeling questions are good: maybe they have to gather some data, construct a mathematical model, cross-check it against reality, and then come to a conclusion about its predictions. In a form suitable for a memo to their boss, whose last math class was “Introduction to ENRON Accounting”)

Wait, you won’t be teaching online next semester because by then the stay-at-home orders will be rescinded?

Sure…but the same issues still apply. Again: If your final exam can be passed by someone using a a free internet app, then what is the value of your course? The “silver lining” of the crisis may be that we scrap the idea of an exam once and forever, and find valid ways to assess student learning.